Last updated on February 19, 2015

Once upon a time In the fall of 2013, I took my paper with Lindsey Novak and Tara Steinmetz on female genital cutting (FGC) on the road. I presented it at invited seminars and at development conferences here and there and received a lot of good feedback before submitting it for publication.

In March of last year, the Journal of Development Economics invited us to revise and resubmit it for publication. One of the best comments we received, however, was that we were only looking at Senegal and The Gambia for the most recent years available, and since there existed comparable data sets for most of West Africa over several years, why not expand the analysis to cover West Africa, thereby gaining in external validity?

And so Lindsey got to work on cleaning 36 additional country-year data sets, i.e., all of the available Demographic and Health Surveys and Multiple Indicators Cluster Surveys for West Africa, for all available years, which included questions about FGC. This occupied us Lindsey for the better part of this last year (and because the data sets are repeated cross-sections which vary a bit in how they were collected both between and within countries, this generated an almost 200-page appendix), but we finally have a revised version of the paper.

You can find the new version of our paper here, and the appendix here, but here is the abstract:

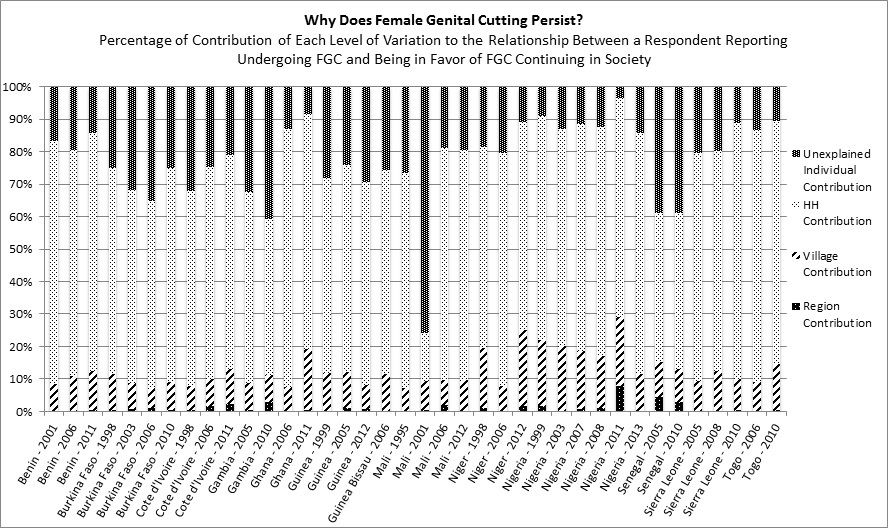

Why does female genital cutting (FGC) persist in certain places but has declined elsewhere? We study the persistence of FGC—proxied for in this paper by whether survey respondents are in favor of the practice continuing—in West Africa. We use 38 repeated cross-sectional country-year data sets covering 310,613 women in 13 West African countries for the period 1995-2013. The data exhibit sufficient within-household variation to allow controlling for the unobserved heterogeneity between households, which in turn allows determining how much variation is due to factors at the levels of the individual, household, village and beyond. Our results show that on average, 87 percent of the variation in FGC persistence can be attributed to household- and individual-level factors, with contributions from those levels of variation ranging from 71 percent in Nigeria in 2011 to 93 percent in Burkina Faso in 2006. Our results also suggest that once invariant factors across women in the same household are accounted for, women who report undergoing FGC in West Africa are on average 16 percentage points more likely to be in favor of the practice.

The following images give the core findings. First, we plot the contribution of each level of variation (i.e., individual, household, village, and beyond) to whether a respondent reports believing that FGC should continue:

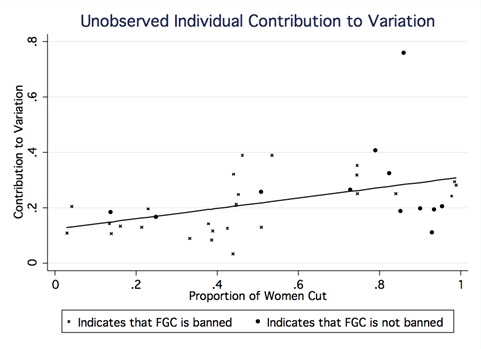

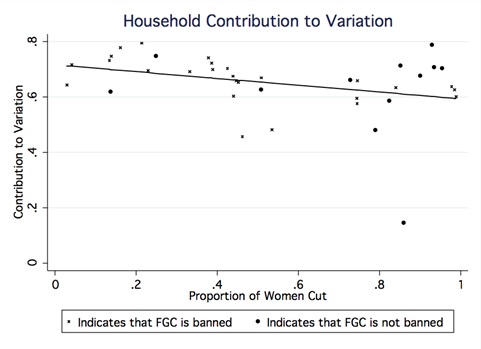

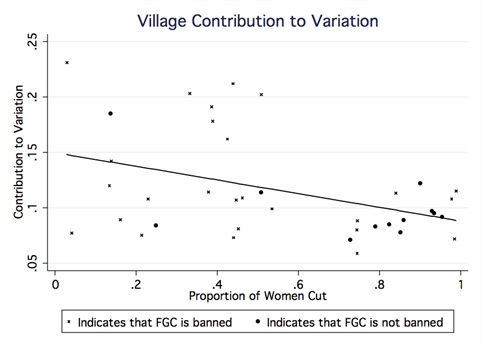

Next, we use the same information to study the relationship between each level of variation and the prevalence of FGC. In other words, are individual/household/village-level factors more likely to drive support for FGC in places where the practice is more/less prevalent? The answer is yes:

As we conclude in the paper:

From a policy perspective, this suggests that as FGC becomes less pervasive, policies aimed at eliminating the practice should increasingly target households and villages, and decreasingly target individuals. That being said, even with a sharp decrease in FGC prevalence, [the second picture above] suggests that the bulk of FGC persistence would still come from household-level factors. This is in contradiction with the tipping point and informational cascade models (Schelling, 1978; Bikhchandani et al., 1992; Bikhchandani et al., 1998) …, wherein the decision to abandon a social norm such as FGC should be entirely individual in places where the practice is highly pervasive.