Last updated on May 24, 2015

A few weeks ago, my posts on quinoa got a second life after a friend of mine linked to them in a Reddit thread titled “TIL Demand for quinoa in Western nations has pushed up prices to such an extent that poorer people in Peru and Bolivia, where quinoa is from, can no longer afford their staple crop.” (Note: TIL stands for “Today I learned that …” – MFB.)

A few thoughts: First, my friend’s comment linking to my posts on quinoa is thankfully the top-ranked comment, which indicates that there is a certain hunger out there for more accurate information than the unfounded emotional appeals peddled by some in the media. Second, Reddit generates a crazy amount of traffic. As in, my blog stats went nuts for a couple days after that thread became active—the folks at Reddit are not joking when they call themselves “the front page of the Internet.”

If you have any patience to read the entire thread of comments, you’ll notice that something that comes up a bit too frequently is comments of the sort “Yeah, sure, maybe farmers are better off, but traders are the ones making the most money off of this.” Those comments typically imply that traders getting rich is a bad thing.

First, let me ask: Even if it were true that the majority of the gains from the quinoa price increase in the last five years were captured by traders instead of farmers, what’s wrong with that?

What I find interesting in those discussions is the often unspoken assumption that traders are parasites. But Marcel Fafchamps has built a good part of his career on studying the behavior of traders in developing countries (see this book for what is perhaps is most complete work on the topic), and lo and behold, traders serve a useful purpose: They connect consumers of stuff with producers of the same stuff, and in their absence, it would often be the case that consumers would not be able to purchase stuff, and it would often be the case that producers would not be able to sell stuff.

Shouldn’t an economic agent which allows markets to operate fully—and which allows both consumers and producers to attain higher levels of welfare via bigger choice sets and increased profits—be somewhat allowed to make a profit, too? In other words, without traders, we’d still be living in a state of subsistence, consuming very few things, and producing a whole lot of stuff for ourselves.

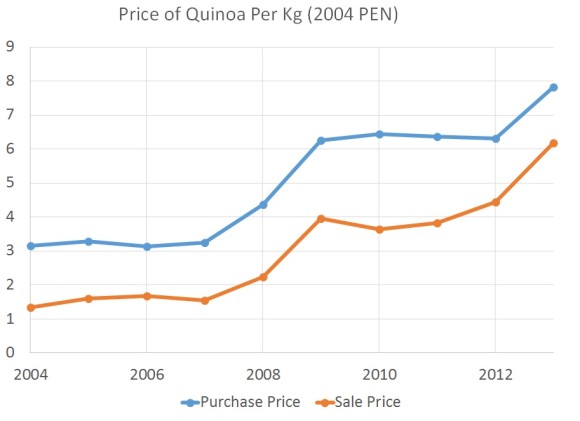

Second, let me debunk the “traders are getting rich” story regarding quinoa. The following graph, which was made by my coauthor Seth Gitter, shows the evolution of the purchase and sales prices of quinoa for the period 2004-2013, expressed in 2004 Peruvian soles:

The first thing that should strike you is that the purchase price is always higher than the sales price. That is all well and good. The difference between the two includes many of the things traders do, viz. buying quinoa from producers, processing it, storing it, shipping it to where consumers live, etc. Notice how the difference between the sales price and the purchase price is surprisingly constant over the period 2004-2013. If anything, it is slightly lessened in 2012 and 2013, when quinoa prices hit the big time. In other words, the “It’s the traders who are getting rich on the backs of poor peasants” stories has very little traction here.

For another, albeit radically different, example of traders being reviled, you can also read this recent NY Times op-ed by Rajiv Sethi titled “The Trader as Scapegoat,” courtesy of Mark Thoma.