Last updated on August 23, 2016

I am teaching an undergraduate class on development microeconomics starting in a few weeks, so I have been reading and thinking about the field quite a bit in preparation for the semester.

One of the things I find striking is how economic theory has regretfully been given short shrift over the past few decades in development economics. This is likely almost entirely due to increases in computing power in the early 1990s,* which led to a much greater demand for data, which in turn fostered more systematic efforts at collecting household survey data in developing countries.**

This made the field of development economics much more empirical than it used to be, and the Credibility Revolution, combined with the rediscovery of randomized controlled trials, came as a one-two punch that pushed the field into almost exclusively empirical territory. And obviously, it didn’t help that the returns to empirical research were much larger than the returns to theoretical research, which had already declined considerably by then.

(To convince yourself of the foregoing, pick up an issue of the Journal of Development Economics from the early 1990s and compare it to one of the most recent ones; the theory-to-empirics ratio has virtually been inverted. Or just think about how the standard text for graduate development micro remains Bardhan and Udry–a book that was published in 1999!)

I am not saying this is good or bad. It just is, and I don’t want to take sides in the age-old debate between theorists and applied econometricians. But given the lack of emphasis on theory in development policy discourses nowadays, I felt as though there was a need for a discussion of some of the core concepts in development economics. If anything, now that we know how to test empirical claims about whether stuff works with a good degree of credibility, attention is turning towards the mechanisms behind how stuff works, and this is where theory is useful.

My Masters advisor used to say: “There aren’t two types of economic analysis, one for developed and one for developing countries; there is only one kind of economic analysis: the right one.” Though that is entirely true, there are certainly certain concepts which need to be brought in in order for economic theory to lead to results that can simply not emerge from the bare-bones neoclassical model/Walrasian frictionless fiction.

To be sure, a lot of the concepts initially developed by development economists are now part and parcel of economic theory; on that topic, see Pranab Bardhan’s 1993 article in the JEP titled “Economics of Development and the Development of Economics.” There was a time, however, when many of those concepts were not exactly mainstream.

A lot of the stuff I hope to discuss in this series comes from old lecture notes and, as such, I owe a huge debt to past instructors.

Heterogeneity

The first concept I wanted to discuss is heterogeneity. The distribution of endowments, for example, is heterogeneous: some households are smallholders and only have a little bit of land; others are large landowners; yet others are landless. Moreover, the land market might be screwed up to the point where land does not get reallocated from the least to most productive households, which means that heterogeneity in landholdings is too important to be assumed away.

That kind of heterogeneity–heterogeneity in landholdings–can lead to another kind of heterogeneity, viz. heterogeneity in market participation regimes, where some households are net buyers of a commodity, others are net sellers of it, and yet others are simply autarkic with respect to that commodity (i.e., they neither buy nor sell it).

Whereas almost all households in a developed country–a situation which we would normally analyze using the tools of neoclassical economics, and for which we would ignore heterogeneity because it is not terribly relevant–would see their welfare increased by a policy whose aim is to keep food cheap, heterogeneity would matter a great deal in the typical developing country. In that case, net buyers of food–city dwellers and the rural poor–would benefit from the policy, and net sellers of food–all of whom are found in rural areas–would be hurt by it.

So whereas the overall welfare effects are not too difficult to figure out for the developed country, they are a lot more difficult to figure out for the developing country. This is especially so if you would like to come up with a mechanism for the winners to compensate the losers.

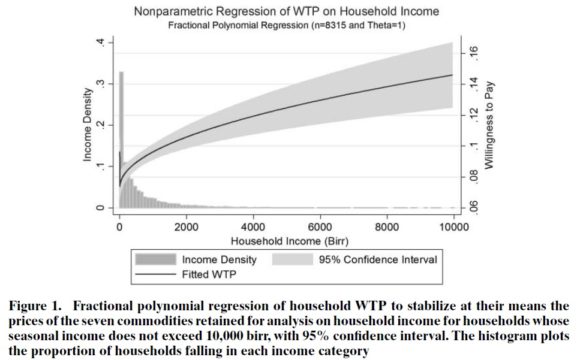

Here is another example. In Bellemare et al. (2013), we estimate the effects of commodity price volatility on the welfare of rural Ethiopian households. Here, it turns out that the qualitative estimated average effect is similar at all income levels–households would be willing to pay a positive fraction of their income to stabilize the prices of the seven most important commodities in the data–but that the magnitude of their willingness to pay (WTP) changes across income levels. The figure below shows how WTP changes as income changes.***

These are only a few examples. There are dozens of sources of heterogeneity which, though they don’t really matter when analyzing economic outcomes in developed countries, often directly drive welfare outcomes in developing countries. The bottom line, then, is this: Those various sources of heterogeneity can not only lead to perverse results, but it is often necessary to take them into consideration in empirical analyses aimed at studying the mechanisms behind the various outcomes we are interested.

* One of the professors I took microeconometrics from during my Masters used to love telling students how one of his summer jobs as a research assistant in grad school had involved inverting a 40 x 40 matrix by hand.

** My colleague Paul Glewwe was one of the early pioneers of household survey data collection. In fact, Paul (and his coauthor Margaret Grosh) pretty much wrote the definitive book on household survey data collection.

*** In a comment on Bellemare et al. (2013), McBride (2015) shows that the shape of that heterogeneity changes depending on how one treats the households in the data who report an income of zero.