Here are some speaking notes I had for the “Getting Published” session at the AAEA early-career professional mentoring workshop held in Atlanta on July 24. I was speaking at a session with two other journal editors, viz. Tim Beatty, from the American Journal of Agricultural Economics, and Ashok Mishra from Agricultural Economics.

First, the notes. Then, some explanation for each of them, since some of them are rather cryptic.

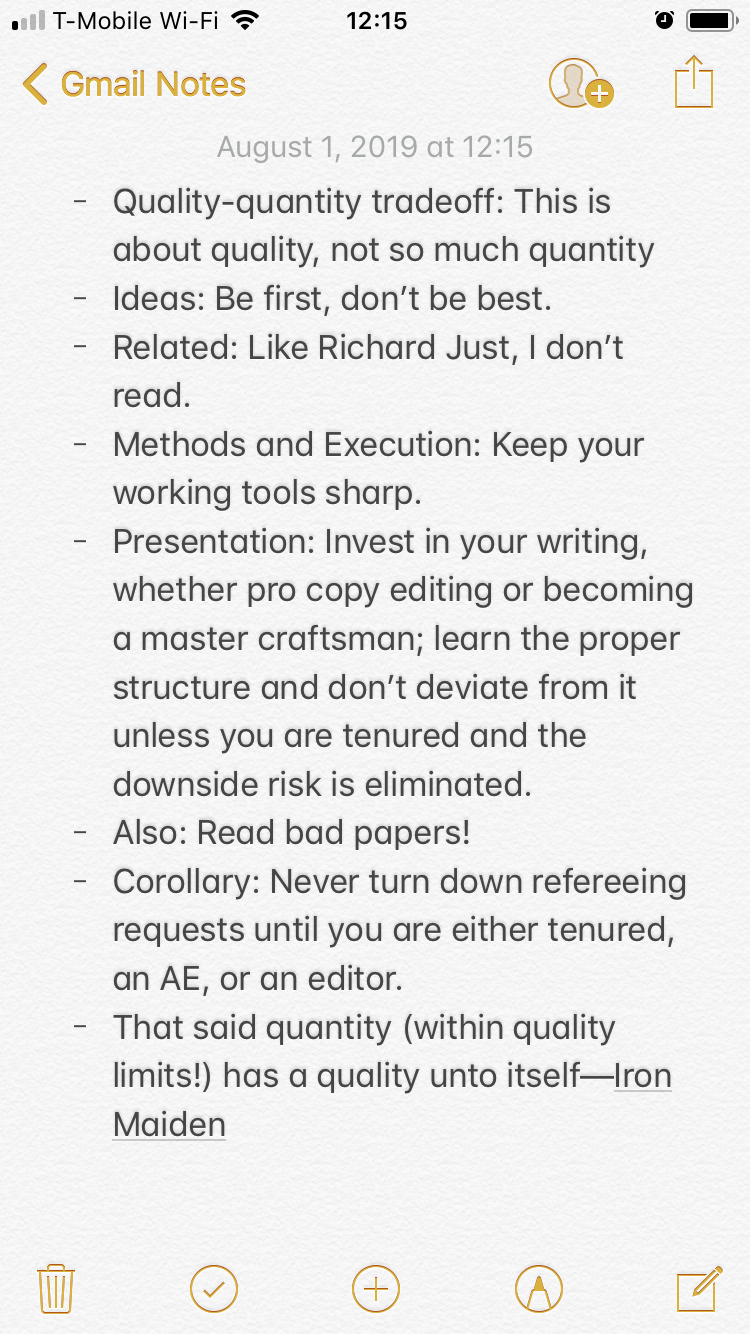

- Quality-quantity tradeoff. Agricultural and applied economics departments tend to be located in agricultural colleges. In such colleges, the majority of researchers operate in so-called bench sciences, which means that they tend to write more and shorter articles than economists do. It is not uncommon for a bench scientist to go up for tenure with 20 articles. For an agricultural and applied economist, in the vast majority of cases, the rule of thumb tends to be this: The number of articles at tenure time should equal at minimum the number of years post-PhD and is usually no more than twice the number of years post-PhD. In economics departments, people tend to go for a lower quantity of articles, each of a higher quality. In agricultural and applied economics departments, it is possible to trade the two off to a point. My talk was meant to push people toward the high-quality end of things. More on this tradeoff at the end of this post.

- Be first, don’t be best. In their 22 Immutable Laws of Marketing, a terrific read for marketing folks as well as for academics, Ries and Trout’s first immutable law is the law of leadership, which states that it is better to be first than it is to be better. No matter what Melania Trump would have you believe with her much-derided “Be best” campaign, my view is that it is better to be first than to be best. That is, it is better to write the first paper on a topic of importance for policy, business, etc. than it is to take an old question and write a better paper on it. Don’t get me wrong: I have written both kinds of papers. But the most rewarding ones have been the ones where I was first to write on a topic.

- I don’t read. This isn’t strictly true, of course. I read plenty of articles as editor, reviewer, graduate advisor, instructor, and so on (though I find it much harder to read for pleasure than I used to, as my threshold for what I find interesting and for what I am willing to read till the end has gone down severely since becoming an academic). I just don’t read academic articles in order to find research ideas. A lot of my research ideas come from reading the newspaper, social media, or going to seminars on other topics and then asking myself whether there is anything I can import into my own research. (For what it’s worth, Richard Just is a legendary agricultural economist who has a reputation for never reading anything, but still writing high-quality papers because of his ideas–and because he works with people who know the literature very well.)

- Keep your working tools sharp. It should go without saying that you need to remain conversant in the methods used in your field. I remember sitting in a seminar ten years ago where a senior colleague was told something like “You can’t use causal language; your variable of interest is endogenous,” and he replied “No it isn’t, Y cannot possibly cause X in this case” … which was true, but also made if painfully clear that the Credibility Revolution had bypassed him, and that he hadn’t internalized the idea that endogeneity is more than just reverse causality. So at the very least, you should read the latest papers in your field (contra the previous rule), if only to remain current on methods. At best, you should read econometrics papers as they get published in order to remain at the cutting edge of methods.

- Presentation. Here, I meant “delivery” more than “presentation,” with the idea that you should communicate your findings as best as you can, whether this involves hiring a professional copy editor (even more so if English is not your first language) or developing a true passion for improving your writing. This also has to do with learning the proper structure for an economics article. If you want to take liberties with that structure, make sure you first master the structure well enough to know how it can be changed (and that you have tenure, even). Before he released the beautiful avant-garde weirdness that is A Love Supreme, John Coltrane worked well within the bebop style on albums such as Relaxin’ with the Miles Davis Quintet.

- Read bad papers. Because it helps a lot.

- Never turn down a refereeing request. At least not until you are an associate editor, editor, or tenured–or unless you already have three or more of them due for other journals. Not only is (good) refereeing the way you build good social capital and become known as a good citizen of the profession, it is also a wonderful way for you to learn what works and what doesn’t work in the papers you read. This is especially true in cases where a journal will also share with you the other reviewers’ comments. (And yes, I fully realize the self-serving nature of this advice given that my success or failure as an editor depends crucially on getting good reviewers to review papers for me…)

- Quantity has a quality of its own. To close the loop on the quality-quantity tradeoff, I have noticed that there are two guaranteed strategies to have an impact as a scholar, where impact is defined by how often your work is cited by others.* The first strategy is to publish fewer, but hugely influential manuscripts. If you are at a top-5 economics department, that is expected of you, and almost nothing else will do. Most of us, however, aren’t a top-5 departments, and most of us cannot even pretend to have One Very Big Idea, much less six to 12 (see the rule of thumb in #1 above) of them. The second strategy is to publish many, many manuscripts on average in decent-quality (e.g., top-field) journals. The scholars whose work I really admire–and who are all cited more than 10,000 times on Google Scholar–pretty much all fall in this category, and what I have observed casually is that the marginal impact of publishing on your citation count is increasing in the number of publications you already have, because every new article will point people to your other works, which they are likely to end up citing. Ryan Holiday has a good story he tells in Perennial Seller about Iron Maiden–a band that is never on the radio or on MTV (and which, to be honest, is not exactly made up of teenage heartthrobs), but which keeps making records, selling them, and touring heavily in support of them 40 years after they released their debut album: Every time they release an album, they sell a whole lot of that album–but sales for all of their other albums also spike!

* Some may disagree. Personally, I don’t care how good of a journal a paper is published in: If the paper is not cited very well, it had little to no impact no matter how good the journal it is published in, and no matter how difficult it was to get published. If a tree falls in the forest and no one is around to witness it, did the tree really fall?