As promised here a few weeks ago, I have just finished revising my paper with Chris Barrett and David Just on the welfare impacts of food price volatility. Here is the abstract:

“Many governments have tried to stabilize commodity prices based on the widespread belief that households in developing countries – especially poorer ones – value price stability, defined here as the lack of fluctuations around a mean price level. We derive a measure of multivariate price risk aversion as well as an associated measure of willingness to pay for price stabilization across multiple commodities. Using data from a panel of Ethiopian households, our estimates suggest that the average household would be willing to pay 6-32 percent of its income to eliminate volatility in the prices of the seven primary food commodities. Not everyone benefits from price stabilization, however. Contrary to conventional wisdom, the welfare gains from eliminating price volatility would be concentrated in the upper 40 percent of the income distribution, making food price stabilization a distributionally regressive policy in this context.”

The counterintuitive result that poor households benefit from price volatility while wealthier households would benefit from price stabilization is, in my view, very interesting. It arises from the fact that poor households are typically net buyers (i.e., pure consumers) of all commodities while wealthier households are typically net sellers (i.e., pure producers) of all commodities.

Producers, however, must sink resources into the production process on the basis of their expectations regarding the price level at harvest, long before the resolution of price uncertainty. Consumers, for their part, can adjust their consumption bundle as a response to prices after the resolution of price uncertainty.

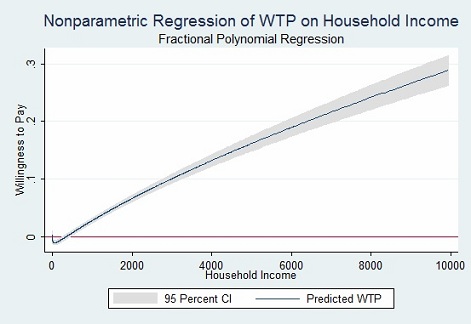

The following graph summarizes the main result of the paper, as it plots household income on the x-axis and the proportion of its income a household is willing to pay to eliminate price volatility on the y-axis:

Note how the poorest households have a negative willingness to pay for price stabilization. In other words, they would need to be compensated in order for their welfare to be maintained at its current level after a price stabilization policy.