Courtesy of one of the students in my development seminar, here are links to a two-part NPR story about China’s famine of 1958-1962: part 1 and part 2.

Between 1958 and 1962, an estimated 20 to 43 people died of hunger in China, which China’s official statistics claiming 15 million deaths and the highest estimates reporting a death toll of 45 million. For comparison, the death toll from World War 1 is estimated to be about 17 million. During the Chinese famine, people eventually survived on anything they could find, eventually going so far as to eat their dead and their own children.

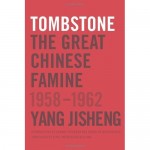

The NPR story discusses Tombstone, a book which just came out in English and which took Chinese reporter Yang Jisheng 10 years of working in secrecy to write. I’m about 100 pages into the book. It is a fascinating and monumental account of China’s Great Famine. And as one might reasonably expect, it is banned in China.

Of Africa — and Writing

With the venerable Soyinka now 78, I wish I could report that his new volume of sweeping reflections is of the same stature as his best work, but sadly it is not. The book is vague, ponderous and awkward. Soyinka never says “house” when he can say “habitation,” “native” when he can say “autochthon,” “dominant” when he can say “hegemonic.” Phrases in quotation marks float free of any source. When he makes broad generalizations and criticisms he sometimes expects the reader to mentally provide specific examples. (Do you remember exactly what President Obama said in Cairo in 2009? I had to look it up.) The book abounds in passages full of 10-dollar words that have to be read two or three times to figure out what they mean. About contentions in Christian theology, for example, he says:

“These all-consuming debates and formal encyclicals are constructed on what we may term a proliferating autogeny within a hermetic realm — what is at the core of arguments need not be true; it is sufficient that the layers upon layers of dialectical constructs fit snugly on top of one another.”

That’s Adam Hochschild discussing Nigerian writer and 1986 Nobel laureate for literature Wole Soyinka‘s new book Of Africa in the New York Times Book Review.