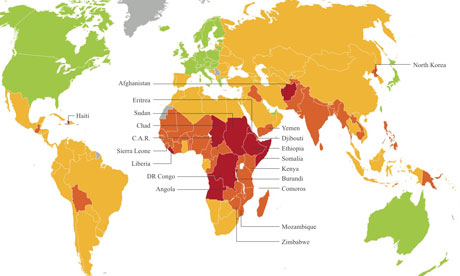

An interesting map showing the risk of food insecurity on Damian Carrington’s blog on The Guardian’s website:

As you may have guessed, green denotes areas where there is a low risk of food insecurity, whereas red denotes areas where there is an extreme risk of food insecurity. Of course, the dark orange and red areas coincide with countries that are often subject to conflict, civil or otherwise. Carrington writes:

And it demonstrates the sickening, symbiotic relationship between lack of food and conflict: where one leads, the other follows.

We must start with the worst, in the horn of Africa. In Somalia, Ethiopia and Eritrea, human failings mean a severe drought has tipped millions into famine. It’s a textbook case of why things go wrong. War begets poverty, leaving food unaffordable. Devastated infrastructure destroys both food production and the ability to truck in emergency food. The collapse of society means the effects of extreme weather such as drought cannot be dealt with. And the fear of violence turns people into refugees, leaving their livelihoods and social networks behind.

To which I say: Let’s not get carried away. The map shows a correlation, but correlation does not imply causation. As such, the map demonstrates nothing except for the fact that there is a potentially statistically significant correlation between hunger and conflict.

For a (hopefully) more convincing argument that actually aims at establishing that there is indeed a causal relationship flowing from food prices to social unrest, see here.

(HT: @viewfromthecave.)