There is less than one month until my book Doing Economics: What You Should Have Learned in Grad School–But Didn’t comes out on May 10.

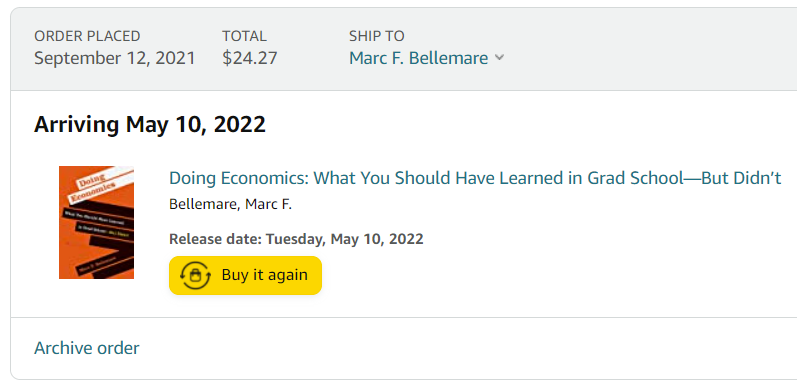

One of the things that most people don’t realize about the book-publishing business is the importance of pre-orders, which act as an early signal of interest in a given book. If you are planning on buying the book, I would like to encourage you to pre-order it here, which will ensure that you receive the book on the day it is released (see the expected delivery date for my own pre-order below), and your credit card will not get charged until your copy of the book ships.

You have pre-ordered your own copy but know someone who is about to enter grad school to do quantitative social science, is already in grad school doing so, or is about to start a position doing so? This would make for a great gift for them.