I’ve discussed this paper often on this blog (see here, here, here, and here), but here goes one last time: My article on female genital cutting in West Africa with Lindsey Novak and Tara Steinmetz is now published on the Journal of Development Economics website, and will be published in the November 2015 issue of the journal.

Here is the abstract:

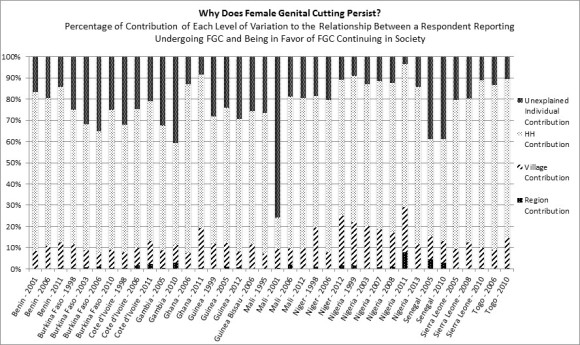

Why does female genital cutting (FGC) persist in certain places but has declined elsewhere? We study the persistence of FGC—proxied for by whether survey respondents are in favor of the practice continuing—in West Africa. We use 38 repeated cross-sectional country-year data sets covering 310,613 women aged 15 to 49 in 13 West African countries for the period 1995–2013. The data exhibit sufficient within-household variation to allow controlling for the unobserved heterogeneity between households, which in turn allows determining how much variation is due to factors at the levels of the individual, household, village, and beyond. Our results show that on average, 87% of the variation in FGC persistence can be attributed to household- and individual-level factors, with contributions from those levels of variation ranging from 71% in Nigeria in 2011 to 93% in Burkina Faso in 2006. Our results also suggest that once invariant factors across women aged 15 to 49 in the same household are accounted for, women who report having undergone FGC in West Africa are on average 16 percentage points more likely to be in favor of the practice.

Once again, here is the key figure from the paper, which shows where support for FGC comes from in West Africa. Note that in most cases, the bulk of support for the practice comes from observed and unobserved factors at the household level which do not vary from one individual to another within the household as well as from individual-level factors, i.e., from levels beyond those of the community: