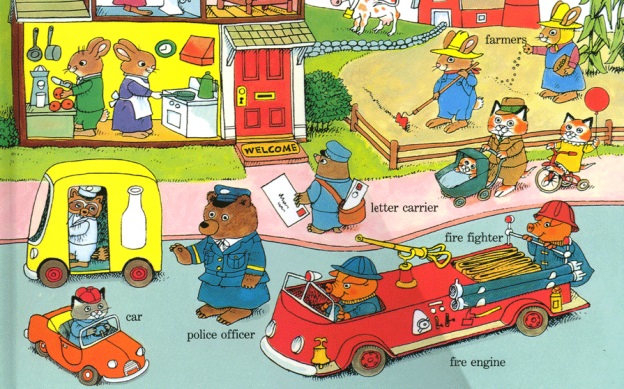

A few years ago, while reporting on the madness that is European farm subsidies, this columnist came up with a “Richard Scarry” rule of politics. Most politicians hate to confront any profession or industry that routinely appears in children’s books (such as those penned by the late Mr. Scarry). This gives outsize power to such folk as farmers, fishermen, doctors, firemen or—to cite a fine work in the Scarry canon—to firms that build Cars and Trucks and Things That Go. The rule is seldom good news for taxpayers, and there is a logic to that too: picture books rarely show people handing over fistfuls of money to the government.

The Scarry rule was tested afresh on March 7th at the inaugural “Iowa Ag Summit,” a campaign-style forum for politicians pondering White House runs in 2016. Reflecting Iowa’s clout as host of the first caucuses of the presidential election cycle, the summit lured nine putative candidates, all of them Republicans. Democrats were also invited, but declined. Such grandees as Jeb Bush, a former governor of Florida, Governor Scott Walker of Wisconsin and Governor Chris Christie of New Jersey took turns to sit on a dais beside a shiny green tractor, to tell an audience of corn (maize) growers, pork-producers and hundreds of reporters how much they love farmers.