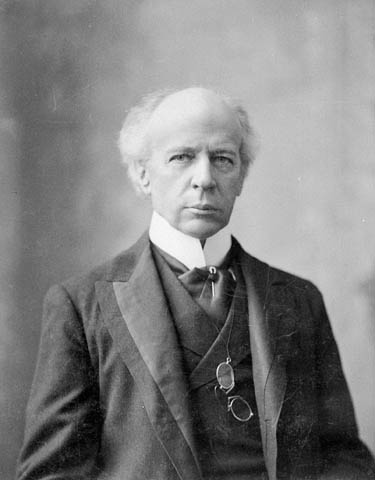

“Quebec does not have opinions, but only sentiments,” once said Canadian Prime Minster Sir Wilfrid Laurier, who himself hailed from Quebec. I was sadly reminded of Laurier’s quip when I read the following op-ed in La Presse (Montreal) on December 30 (what follows is a mixture of my own translation and Google Translate):

The media reports a recent spate of land purchases in Quebec by investment banks. Given the financial difficulties of farmers, those financial firms appear to have smelled a bargain. Some farmers are faced with a lack of succession within their families. Others are facing debts due to having chosen to get into a more industrialized form of agriculture.

But this multiplication of land purchases and the operation of agricultural land by large landowners likely heralds a return to sharecropping.

Without going into the details of the institution of sharecropping, a few centuries ago, large landowners leased their lands out to farmers with whom they agreed to share the harvest. In short, those landlords agreed that part of the tenants’ agricultural labor, of which they appropriated the benefits, could go to the tenants themselves. Those tenant farmers were more or less agricultural laborers.

The gradual emancipation of the peasantry favored a mode of production centered on the family farm. But in the last few decades, industrialization has come to pervade all areas of production, agricultural production included. This has led to the situation we see today, viz. the coexistence of family farms with other farms focused on intensive large-scale production.

With this purchase of large tracts of land in Quebec by investment banks, we return in some way to the sharecropping system of centuries past: Peasants again are becoming agricultural laborers whom landowners allow to use a plot of land for their subsistence. It is hard to imagine that such an approach represents any kind of progress.

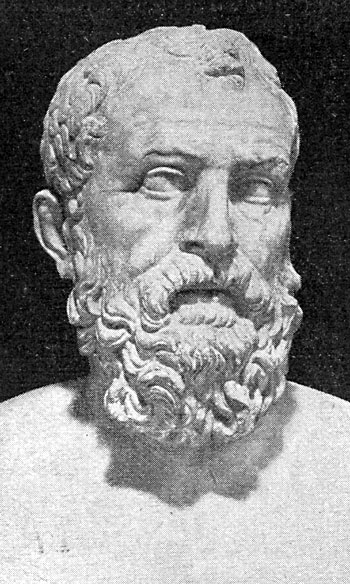

“In all things let reason be your guide,” said Athenian statesman Solon. After blogging about agriculture-related matters for over three years in an effort to inject some rational thought in policy debates, I thought I had seen all kinds of irrational arguments, but the above op-ed takes the cake.

First off, it is important to differentiate between the three types of agricultural contracts a landlord can enter with a tenant:

- A fixed rent contract, wherein the tenant pays a fixed amount of cash in exchange for the right to use the land, with the tenant getting the entirety of the crop. In this case, the tenant bears all of the risk inherent in agricultural production (e.g., weather, natural disasters, pests, etc.)

- A sharecropping contract, wherein the tenant pays a share of the crop in exchange for the right to use the land. In this case, the landlord and the tenant share the risk inherent in agricultural production at the same rate at which they share the crop (e.g., if the landlord receives 60% of the output, she bears 60% of the risk).

- A wage contract, wherein the landlord pays the tenant a fixed wage in exchange for the tenant working on the plot, with the landlord getting the entirety of the crop. In this case, the landlord bears all of the risk inherent in agricultural production.

It is only in the third type of contract that the “tenant” (who is no longer a tenant) becomes an agricultural laborer. Moreover, there is no shame in being an agricultural laborer: Many peasants the world over would like nothing more than to get a steady paycheck for their work rather than face the vagaries of agricultural production.

Also, it is really not clear what type of contract the investment banks will choose to sign with whomever they choose as their tenants. My hunch is that they would go for fixed rent or wage contracts: the former because it allows charging the highest amount of rent (in monetary value) and because there are a number of insurance programs for agricultural producers, the latter because it could be the case that those investment banks can hire good managers, because agricultural labor tends to be cheaper than more skilled labor, or because investment banks are simply in a much better position to shoulder risk. So to assume that they will choose sharecropping contracts is just that–an assumption, and not a very good one at that.*

Second, the author is fundamentally mistaken about the institution of sharecropping. It is bon ton for authors in the humanities and in the social sciences (outside of economics, that is) to vilify the institution of sharecropping. This largely owes to the fact that sharecropping was the dominant choice of contract for wealthy white landowners contracting with poor, recently emancipated black tenants in the postbellum South. But in truth, and as I have alluded to above, the institution of sharecropping has been observed the world over, and it almost always constitutes a rational response to missing insurance markets. To show that this was true was one of economics Nobel laureate Joe Stiglitz’s first (of many) major contributions to economic theory, in a 1974 paper titled “Incentives and Risk Sharing in Sharecropping.”

Third, the author employs a form of dog-whistle politics when he talks of the “peasantry” (throwing an entire category of people into an imagined oppressed “class” is bait for those city folk who know nothing of agriculture, economics, or agricultural economics). Finally, the author commits the logical fallacy of appeal to emotion by saying that because sharecropping was common in the past, the fact that (the author thinks) it is resurfacing again today hardly represents “any kind of progress.”

With that being said, when one of Montreal’s most widely read newspapers publishes that kind of rubbish, it is difficult to believe things have changed very much since the turn of the last century, when Wilfrid Laurier was Prime Minister.

* But what do I know? I’ve only written an award-winning PhD dissertation on the topic of agrarian contracts, two thirds of which was about sharecropping…