Last updated on October 25, 2015

A question from one of our PhD students:

Hi Marc,

I have a general question about reading references. How do you usually do reference reading? Do you take some notes in any software in your computer? How can you recall the main ideas of a specific paper after you have read a lot relevant papers?

Do you know or have you written any (blog) article about how to read academic references for graduate students?

At first, I had no idea how to answer that question, but then I remembered that a long time ago, Kim Yi Dionne wrote a post addressing just that.

That said, let me state the obvious: You can’t read academic books and articles like you read novels or magazine articles, and developing the right method for reading academic articles is key to becoming a more effective researcher. The way I went about it was pretty simple: I just read, read, and read some more until I developed some good habits, which I can summarize as follows:

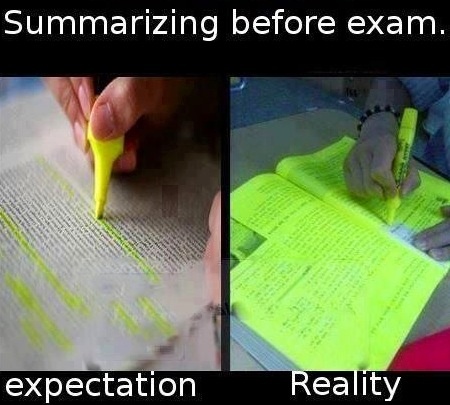

Read with two pens in hand, one a highlighter, and one a regular pen. Use the highlighter to highlight what you think is important, and use the pen to take notes in the margins.

I developed my “method” starting with the literature review I did for my Masters thesis. I remember having to read Stiglitz and Weiss (1981), and in order to follow the math, I would write down the variable names and equations and then try to reproduce the authors’ derivations in the margins.

And when I decided to read everything I could find on contract theory and applied contract theory when writing my dissertation, I went about it the same way. I made sure to keep a bibliography of all the articles I was reading, both so I could remember what I had read, but also so I could easily copy and past them into my dissertation or a research paper when necessary.

With books, of course, it is a bit more difficult to use this method, first because the books might not be yours, and then because you might not want to deface your books. Luckily, I also happen to be in a discipline where most of the literature consists of articles, which I can print and read (this is important: I don’t recommend reading articles on a computer or tablet, simply because it is easier to remember things you read on paper than things you read electronically, and because it is easier to highlight and annotate on paper). But generally: If a book is important for your research, it is perhaps best to buy it or photocopy the relevant parts, and academic books are not exactly like previous first editions of famous classics, so I personally feel free to deface them by highlighting and annotating them.

(Some people like to do this with EndNote, which you can use to format your bibliography in a given journal’s style with a few clicks. Unfortunately, after starting many times with EndNotes, I never got the hang of using it, and I decided to uninstall it.)

That’s it, really. I don’t think there is anything more to it than highlight and take notes in the margins, which combined with the increasing returns to scale that come from reading enough academic articles, will make you a more effective consumer of scientific literature. Some people might recommend reading the abstract, introduction, and conclusion at first, which is not a bad idea if you want to know where a paper is going, but I still recommend reading everything–at least to grad students. When you become a more experienced reader, you’ll have a pretty good sense of what you can skip, but this can be risky in grad school when you are less familiar with what is important and what is less important.