Last updated on June 5, 2022

My chapter with Jeff Bloem and Sunghun Lim titled “Producers, Consumers, and Value Chains in Low- and Middle-Income Countries,” which we wrote for the sixth volume of the Handbook of Agricultural Economics, is finally out, and freely available for download until July 12. Get it while you can! (And if you read this after July 12, 2022, email me for a copy.)

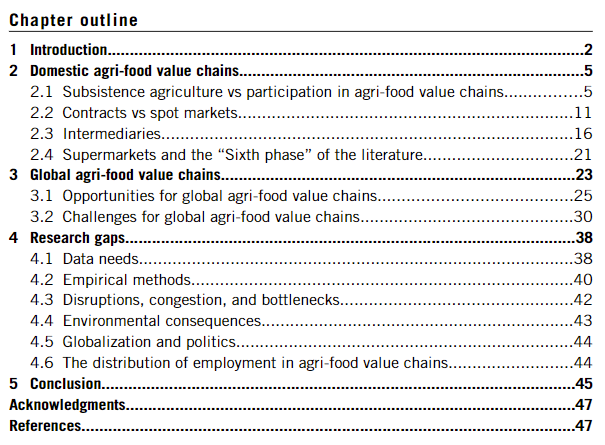

Here is an outline of the chapter:

The task of summarizing the literature on agricultural value chains was a monumental one given how much of it there is. That task was made even more monumental because we wanted to summarize both the literature on within-country value chains (i.e., how agricultural commodities go from the farm gate to final consumers or exporters, in section 2), which is what Jeff and I have written about, as well as the literature on between-country value chains (i.e., global value chains, or how agricultural commodities that may be produced in a given country end up consumed in another, in section 3), which is what Sunghun has written about.

Anyone interested in this topic can be brought up to speed by reading sections 1 to 3. But for me, most of the value added of this chapter is in the future research directions we lay out in section 4. This should be of interest to graduate students, early-career researchers, and others interested in working in this area, where new thinking is required, as I have made the case here and there. The research gaps we identify are as follows:

- Data. While there are good systematic value-chain data collection efforts on within-country endpoints (i.e., agricultural producers on the one hand, and consumers and retailers on the other hand), very little data are systematically collected on the middle of value chains (i.e., trader, processors, wholesalers, and so on. But if we wish to gain a better understanding of value chains, we cannot rely on theory and anecdotes.

- Empirical Methods. Empirical studies in this area typically consist of case studies or of design-based causal inference studies looking at a given dyadic link, i.e., a link between two agents, such as growers and processors in the contract farming literature. But if we wish to understand how commodities (not just food, but all commodities) get from producers to consumers, we need a bigger-picture (in the limit, whole-value-chain) understanding, and this is something case studies and design-based applied micro studies cannot give us.

- Disruptions, congestions, and bottlenecks. The one-two punch that was the global pandemic and the Russian attack on Ukraine have made pretty clear that we need a better understanding of what makes a given value chain resilient or not. Many countries are now rethinking their supply chains of food, batteries, microchips, and so on. While I am wishing for a return to 2019-style global trade, I suspect those days are over, and we need to have a good understanding of the causes and consequences of supply-chain disruptions.

- Environmental consequences. If a country decides to produce something domestically rather than import it from China, there are some environmental tradeoffs in terms of miles traveled and the likely pollution domestic production that this would cause domestically. More simply, greater integration in global value chains typically means that consumers require a more stable supply of a given commodity, and this often comes at the cost of more industrial production, which tends to damage the environment more than small-scale production. While there is a “new” field of “envirodevonomics” that has looked at the impacts of industrial production on a number of outcomes (e.g., child mortality, educational attainment), it has as far as I know largely ignored the consequences of greater industrialization because of greater participation in global value chains.

- Globalization and politics. We are starting to get a pretty good picture of the impacts of globalization on politics, at least in high-income countries: The displacement of manufacturing jobs has led to the rise of populist movements via a disenfranchisement of working-class voters, who have either had to get more education or accept lower-quality (if not lower-dignity) services jobs. Two open questions here: 1) What will happen in middle-, then low-income countries if and when they experience a similar transformation?, and 2) What will happen in high-income countries if they decide to disengage from international trade, and produce domestically in the future more of what they are now importing, and “bring manufacturing jobs back”? I strikes me that question 1 should be on the radar of folks working on the political economy of development, and question 2 is wide open for scholars of American politics and labor economists.

- Labor. The distribution of labor among value chains follows predictable patterns given the structural transformation, but changes to the distribution of labor require changes to labor laws, social programs, the regulation of market power, and so on.

Our avowed goal with this chapter is to “launch a thousand ships” in the form of generating new, original, and exciting research. To that end, we have sought to make this as accessible as possible. We hope it becomes a reference on this topic for the next several years.