As a result of having served as editor of Food Policy (2015-2019) and the American Journal of Agricultural Economics (2019-2023), I’ve been asked to write a lot of tenure and promotion letters these past ten years. This has given me a chance to reflect on how people can be successful in agricultural economics. Given that, I thought I should uncover some of the hidden curriculum behind how people’s research portfolios are evaluated on the job market, for tenure, for promotion, and so on.

But first, what does “successful” mean? This is where objective criteria come into play, but I can think of several proxies for success.1 First, there is success at the extensive margin: Does someone get tenure? Do they get promoted? Are they considered for endowed chairs or named professorships? Second, there is success at the intensive margin: How many Google Scholar or Web of Science citations does someone have? What is their h-index? What is their salary relative to comparable matches? And then there is stuff like the kind of job offers they get when they go on the market.

“Quantity has a quality all of its own,” a mentor once told me. By that, he was alluding to the fact that while some researchers in our discipline (i.e., agricultural economics) are known for publishing high-quality articles, others are known for publishing a high quantity of articles, and that publishing a high quantity of articles can eventually add up to quality. I wanted to talk about quantity, quality, or even both can be leveraged in terms of having a scholarly impact.

Quality

I think there is broad agreement on what “quality” means in agricultural economics: Assuming a research article in the American Journal of Agricultural Economics (AJAE, i.e., the journal in agricultural economics) is the numéraire (i.e., the yardstick by which other publications are evaluated), we can express other publications in terms of AJAE equivalents.

While the precise value of each publication does remain subjective, there is widespread agreement that an article in a top-five economics journal is definitely worth more than one article in the AJAE. For an article in a general science journal like Nature, Science, of PNAS, opinions differ. Some people will view those as > 1 AJAE. Others will view them as ≈ 1 AJAE. Yet others will view them as < 1 AJAE. Articles in top field journals (e.g., Journal of Development Economics, Journal of the Association of Environmental and Resource Economists), will usually be worth 1 AJAE, if not more. Articles in regional agricultural economics journals will usually be worth < 1 AJAE. Predatory or near-predatory journals tend to be worth 0 AJAE.2 Given that rough ranking, people typically have a subjective criterion for how much quality they want to see.

Quantity

Quantity might lead to quality a few different ways. First, black swans do crop up. If someone publishes five or six articles year in, year out, eventually one of them is bound to be in the far-right tail of the quality distribution. To see this, look at Woody Allen’s filmography here. Whatever one might think of him, in the 58 years between 1965 and 2023, there were only seven years during which Woody Allen did not release a film he either directed, wrote, or acted in. Of the 65 films he did release (did I forget to mention there were 10 years where he released more than one?), only three won an Oscar: Annie Hall, Hannah and Her Sisters, and Midnight in Paris. Unless you’re a film buff, odds are those are the ones you’ve heard of.

The same can happen with research. If you publish five to ten articles a year, the Law of Truly Large Numbers says that every once in a while, you’ll put out a real banger. If you’re econometrically minded, call that a within-article quality effect.

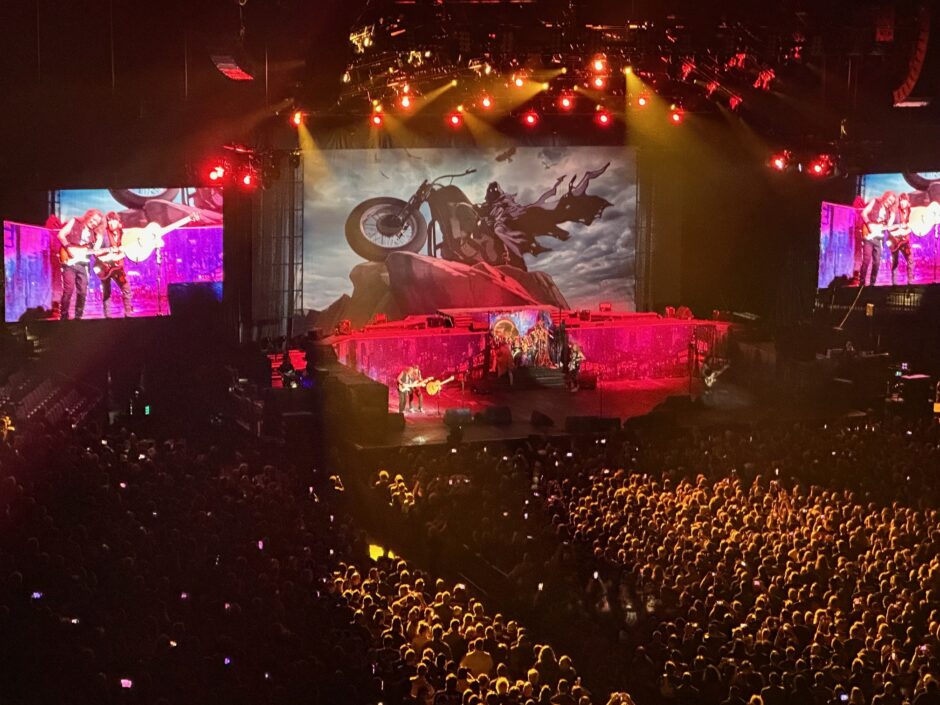

Second, if “quality” is defined as the number of citations to one’s work,3 quantity can generate citations-as-quality via spillover effects. To see this, consider the following anecdote told by Ryan Holiday in Perennial Seller, I think. Iron Maiden has never gotten much airplay. They’ve always been a band that few if any radio stations would touch. And yet they’ve been around since before I was born, they’ve put out 17 studio albums and 13 live ones, they keep touring and selling out hockey arenas and, for a time, they even had their own jet airplane.

How did they do it? By releasing either a studio or live album every few years. As Holiday explains it: Every time they release a new album, not only do they sell a lot of that album, they sell a lot of their other albums, too, because people are reminded of Iron Maiden and of their other albums.

If you’re a researcher, this is the type of thing that happens if you become known for working on a given topic, since people will typically cite work by the same author in clusters.4 Again, if you’re econometrically minded, call that a between-article quality effect.

Quantity or Quality?

Which of quantity or quality should a researcher target? I think it is reasonable to say that one should avoid corner solutions at all costs. That is, one should avoid focusing purely on quality, and one should avoid focusing purely on quantity. I used the term “portfolio” above to describe the sum total of someone’s scholarly output. I used that term for a reason: Just like you would not want to put all your retirement savings in a single stock, you also would not want to spread your retirement savings across too many stocks. (Ignore mutual or index funds, since there are no such equivalents in publishing.)

What is the right balance of quality and quantity for you? That depends on the incentives you face. In other words: It depends on the job you have, or on the kind of job offer you would like to get if you are in grad school (or if you have a job but would like to get a competing offer).

Some departments will want to see quality above anything else. Others will be happy to let you substitute as much quantity as you want for quality. The one pattern I am aware of here is this: The closer you get to the top in terms of departmental rankings, the less quantity is acceptable as a substitute for quality. At the very top departments, the elasticity of substitution is zero: No amount of quantity can make up for a lack of quality.

Beyond individual-level strategies, this suggests the following institutional-level strategy: If a department wants to work its way up the rankings, it is probably wise to invest in significantly more quality at the expense of quantity. Conversely, a department that encourages quantity is unlikely to move up the rankings.5

- Those are proxies for success since everyone has their own subjective criteria for what constitutes success, and so in the absence of data that allow comparing subjective outcomes, we can only go by external signals if we want to quantify “success.” ↩︎

- For some, an article in a predatory or near-predatory journal may even reduce the quality of someone’s research portfolio, i.e., be worth < 0 AJAE, because it shows a lack of judgment. ↩︎

- While some citations are clearly better than others, the vast majority of citations are neither good (e.g., a citation from a Nobel laureate, or from an article in a top journal) nor bad (e.g., a citation from an article that criticizes you for being wrong about something, or a citation from a predatory journal). At any rate, while you may not like citations as a measure of impact or quality, your dean, various funders, and colleagues in other departments certainly do, as citations are the only thing easily compared across disciplines. Even the RepEc ranking of economists relies on citations. ↩︎

- For example, suppose someone is working on a topic Someone named Smith worked on. Very often, instead of citing the one or two most relevant paper by Smith, they’ll cite almost all or all of Smith’s output on the topic. They do so for two reasons. First, most people don’t spend much time reading. They’ll remember “Oh, right… Smith said that one thing about this topic. Wait, where did she say it? Ah, screw it. Let’s just cite everything.” Second, they may also do so strategically, to increase the likelihood that Smith will be one of their reviewers. ↩︎

- For instance, I know a department where, in order to get tenure, someone on a 50-50 teaching-research split has to publish at least 2.4 articles per year. Given how much an article in a top field journal requires, this requirement is hardly conducive to that department going up in rankings. ↩︎