Last updated on September 8, 2013

A recent Twitter conversation I had with other social scientists made me reflect upon the state of my own discipline when it comes to standards of evidence. That is, about when we can say that we are fairly certain about a specific conclusion drawn from analyzing data.

The conversation began when Raul Pacheco-Vega said “I love experimental methods, but being obsessed with it is unhealthy.”

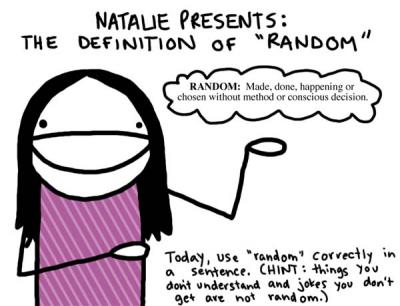

I responded that what is unhealthy is the attitude according to which “the only good research questions are the ones that can be randomized.” That is, the mode of thinking – dominant among certain empirical economists – according to which if a research question does not lend itself to randomization, it is not worth one’s time to try answering that research question.

The Gold Standard

Now, don’t get me wrong: I recognize that randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are the gold standard of epistemology. To truly know whether we know whether X causes Y, the best empirical trick at our disposal is to conduct an experiment wherein we assign the values of X ourselves at random – what we refer to as randomization – and then test whether Y changes as X changes.

As such, if a question lends itself to randomization, then by all means one should use randomization to answer that question.

The Golden Mean

The problem, however, is that not all questions readily lend themselves to randomization. To take an extreme example from the work I have been doing on female genital cutting (FGC), it would be incredibly difficult (and ethically questionable, if not downright evil) to randomly assign little girls to a treatment that consists in them undergoing FGC, just to see if it changes their perception of the practice.

For most questions, there exist imperfect ways of making causal statements. In some cases, one can find an instrumental variable that is plausibly exogenous to the outcome of interest. But instrumental variables can be difficult or impossible to come by.

In other cases, one can collect panel data and use fixed effects. But panel data are costly to collect and besides, they do not always allow one’s research design to satisfy the stable unit treatment value assumption.

In other cases still, one can exploit some kind of discontinuity in how a treatment is assigned or a natural experiment. But such discontinuities and natural experiments are rare, and very few questions lend themselves to those methods.

To take another example from the work I have been doing on farm bills, it would be impossible to randomize over the amount of PAC monies legislators receive, the electoral makeup of their congressional districts, or whether they themselves have worked in agriculture. In that case, the epistemological difficulty is compounded by the fact that my coauthor and I are trying to test between competing theories of legislative behavior. In other words, we look at three “Does X cause Y?” questions instead of one.

Even in the face of those difficulties, there are some people for whom the only acceptable empirical evidence is that which comes from an RCT. But at the end of the day, “randomization or bust” sounds more like a party line than a sound epistemological position.

My own view is that as in many other things, there is an epistemological golden mean. That is:

- One the one hand, for those questions where we already have tons of observational evidence and/or randomization is feasible, then one should use randomization in coming up with answers.

- On the other hand, for those (many more questions) where the evidence is scarce and/or where randomization is just not possible, then one should recognize that the best available evidence will not come from randomization. In the most extreme cases, the best available evidence may come from (egad!) sound theoretical modeling. Such is often the case in quantum physics.

A gold standard is what it is, but just as the Gold Standard was abandoned in favor of fiat money in 1976, there are instances where the gold standard of RCTs remains a theoretical ideal that must be abandoned because it cannot help us answer important policy questions in practice.

Because of those cases, the “randomization or bust” rhetoric borders on intellectual terrorism, and it is high time that economics and other social sciences develop a protocol delineating what constitutes acceptable empirical evidence at each one of the phases of research.