Last updated on January 6, 2012

If you have taken a principles of economics class, you know that everything else equal, an increase in the price of a good means that you can afford less of that good. So if you value a given good, the consequence of an increase in the price of that good is that you are worse off.

If you live in the United States, your household dedicates about 13 percent of its budget to food. But if instead you lived in a developing country, that figure would be well over 50 percent.

It should thus come as no surprise that increases in the price of food are especially bad for the poor in developing countries. (…)

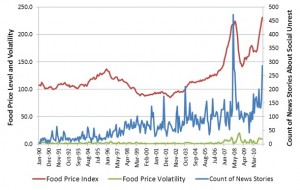

[A]fter attaining a peak during the summer of 2008, food prices started rising rapidly again in the second half of 2010 to hit an all-time high in March of 2011.

Likewise (…) the 2008 and 2011 spikes in food prices coincided with spikes in the number of food riots reported in the news.

But as I constantly remind the students in my development seminar, correlation is not causation, and a key component of critical thinking is the ability to question correlations presented as causal claims. In other words, social unrest may lead to high food prices just as much as the opposite is true.

That’s me in a guest post over at the Woodrow Wilson Center’s New Security Beat blog, in which I explain how I overcome the problem to show that rising food prices most likely cause social unrest.