Some of us development folks work very hard to dispel the notion that Africa is the so-called “Dark Continent,” and that not all news coming out of Africa is bad. As Binyavanga Wainaina wrote very sarcastically some time ago in Granta magazine:

Always use the word ‘Africa’ or ‘Darkness’ or ‘Safari’ in your title. Subtitles may include the words ‘Zanzibar’, ‘Masai’, ‘Zulu’, ‘Zambezi’, ‘Congo’, ‘Nile’, ‘Big’, ‘Sky’, ‘Shadow’, ‘Drum’, ‘Sun’ or ‘Bygone’. Also useful are words such as ‘Guerrillas’, ‘Timeless’, ‘Primordial’ and ‘Tribal’. Note that ‘People’ means Africans who are not black, while ‘The People’ means black Africans.

According to Wikipedia, the expression “dark continent” comes to us from the 19th century, when it was “used to describe Africa, particularly Sub-Saharan Africa. As Europeans knew little about the continent’s interior geography, map-makers would often leave this region dark.”

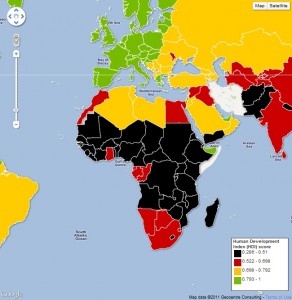

I was thus very surprised that the Guardian — of all newspapers in the world, perhaps the one that cares most about development — would publish the following map to illustrate the 2011 distribution of the United Nations’ human development index:

That’s right.

Malthus, Africa’s Albertine Rift, and Underappreciated Development Economists

From an article in the November 2011 issue of National Geographic magazine on Africa’s Albertine Rift:

By the mid-1980s every acre of arable land outside the parks was being farmed. Sons were inheriting increasingly smaller plots of land, if any at all. Soils were depleted. Tensions were high. Belgian economists Catherine André and Jean-Philippe Platteau conducted a study of land disputes in one region in Rwanda before the genocide and found that more and more households were struggling to feed themselves on little land. Interviewing residents after the genocide, the researchers found it was not uncommon to hear Rwandans argue that “war is necessary to wipe out an excess of population and to bring numbers into line with the available land resources.” Thomas Malthus, the famed English economist who posited that population growth would outstrip the planet’s ability to sustain it unless kept in check by starvation, disease, or war, couldn’t have put it more succinctly.