From a BBC news article:

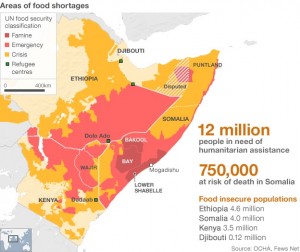

Three months after famine was declared in Somalia, the scale of the crisis in the Horn of Africa remains huge, says a British official.

International Development Secretary Andrew Mitchell said hundreds of people, mainly children, were dying every day.

The coming rainy season is expected to bring disease to crowded refugee camps.

In Somalia alone, Mr Mitchell points out, more than 400,000 children remain at risk of death.

While the rains can bring more misery and death in their wake, they can of course be part of the recovery from this disaster too.

What I find puzzling is the title of the article: “East Africa Drought ‘Remains Huge Crisis’.”

Sure enough, the drought in East Africa is the worst in over 50 years. But to blame it for the famine is a huge stretch. After all, many other areas of the world have experienced drought in the past without then experiencing famine.

More convincingly, why is it that Somalia is experiencing famine, but that Kenya and Ethiopia are not? The different institutions on either side of the Kenya-Somalia and the Ethiopia-Somalia borders make for a nice social experiment and point to the idea that famines are man-made.

In other words, while natural disasters can certainly cause food shortages, it really looks as though bad institutions — the lack of government accountability in most cases — are really the root cause of famine.

For more on the current famine in the Horn of Africa and its human causes, I encourage readers to listen to this excellent podcast.